Retrieval practice is something which has transformed my teaching since I first read about it in Kate Jones’ excellent book Love to Teach. It’s fair to say that now every lesson I have includes some element of retrieval and even fairer to say that my skill at using such strategies has greatly improved with understanding of the nuance behind the approach. So how have I done this?

The principle of retrieval practice is that it helps us to know more by forgetting less. If we look at Ebbinghaus’ Forgetting Curve, we can see that forgetting is a natural part of the human brain and that we lose most of what we are initially taught.

However, all is not lost. If we do use retrieval effectively we can combat this. Essentially by using frequent retrieval of key information, we strengthen the connections in our long term memory, making us more likely to remember the information.

This becomes even more important when we take into consideration what learning actually is.

“Learning is a change in long-term memory.”

“Memory is the residue of thought.”

Kirschner, Sweller and Clark

Daniel T. Willingham

Learning happens over time, not in a 50 minute block of time. Therefore it is important that we return to what we thought we taught to ensure it has been fully encoded into the long term memory. If indeed learning is about remembering and that we remember only what we think about then we need to be drawing student’s attention to the most critical and important aspects of our curriculum to ensure these are prioritised. This therefore means that we must be considering retrieval practice in our curriculum design, not as an afterthought, but as one of the drivers of curriculum content and lesson planning.

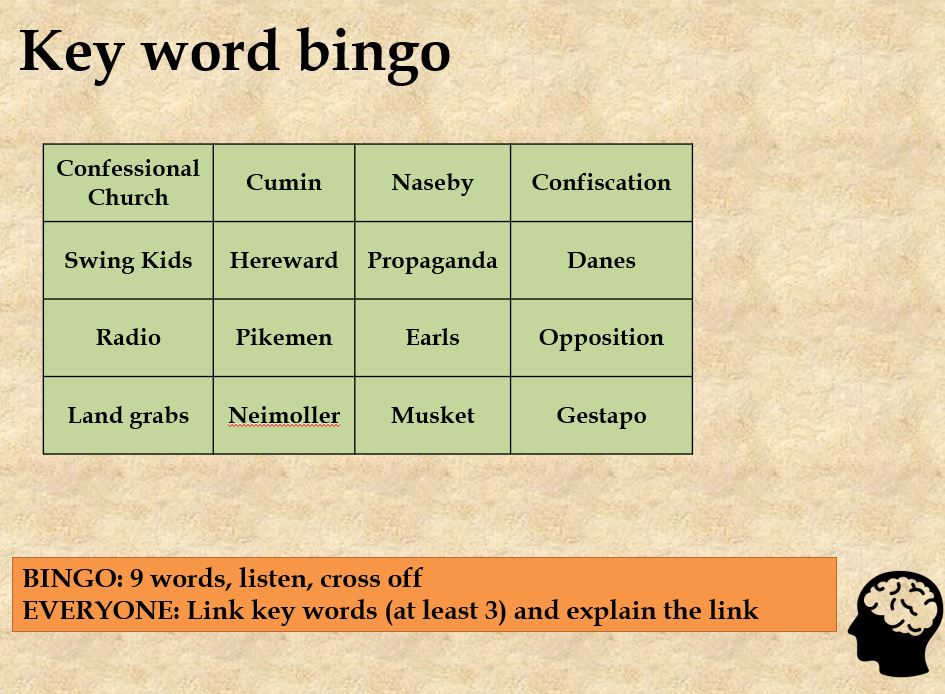

So, if this is as important as I say then how have I embedded it within my own curriculum and lessons? This is an ongoing process and one which I feel, I will always be tweaking and learning from each year. To begin with, my first aim was simply to start using it within lessons. On my return from maternity leave in 2019 I first trialled approaches in my classroom and then did my first whole school presentation on retrieval practice. This focused on different strategies to encourage staff to rethink what they were already doing and be more deliberate in their choice of activity and which knowledge to retrieve. This was, of course, underpinned by the science behind the approach. We have since led multiple sessions, returning to and refining our approach until we have reached a point where both staff and students can identify retrieval activities and explain why they are used. This has not been a case of prescriptive activities but instead a process of trialling and adapting ideas for different faculties to find out what works for them. Some have utilised retrieval booklets, others have focused on knowledge organisers as the main knowledge focused on, some have regular quizzing formats and others more creative ways. What is apparent, however, is the impact this has had on improving the quality of education in our school.

From the initial point of implementing strategies my understanding has grown and developed. Within the History department, we have gone through several stages of embedding retrieval practice:

Step 1

I started with a curriculum review where we identified what the key knowledge from each our main KS3 topics was and therefore used this as a point of reference for assessments and lesson foci. This has been tightened up even further over the last couple of years but our starting point was simply a list. This was initially a hard sell to some who had been teaching for a long time but as they always do they went with me and started to embrace it. At this point, we were all doing our own thing with the knowledge – different questions, slightly different focus, different techniques but it was a clear starting point.

Step 2

This was about specifying to the students what they should know. We started this with knowledge organisers for each unit. We then considered what knowledge we wanted them to be aware of by the end of KS3 – what were the core things we wanted students to be able to talk about by the end (for some of them) of their study of History within school. We then created the resource below – this is more conceptual than specified knowledge but this is what we draw on for our thrice yearly formal assessments. Students are provided with this and as it is utilised for every assessment they begin to retain more and more over KS3. We have one of these for each year at KS3. This supplements the more in depth knowledge organisers that specify the knowledge for the current topic and aren’t necessarily things we want them to know forever (see the excellent blog by Jonathan Grande on this topic).

Step 3

Finally, our latest development; formalising how and when we implement retrieval in the classroom. As we have completely redesigned our KS3 curriculum over the last year or so there was the opportunity to build in pause points. I borrowed the excellent idea of ‘Nothing New Just Review’ lessons from Darren Leslie, as well as building in revision lessons where we have explicitly taught revision techniques which utilise the principles of retrieval and spacing. This has allowed us the opportunity to flexibly decide when and where this is necessary and assess our students knowledge through retrieval activities as well as giving us a chance to consolidate or reteach anything that crops up as a misconception.

All of this has been applied at GCSE as well. I initially designed a 5-a-day (credit Rebecca Bailey) homework booklet to fill in gaps but now this is something that all my Y11 GCSE History students complete weekly, giving them a chance to retrieve the 3 topics we teach in Y10. This rotates through each paper therefore spacing out the topics and we then refer back to this in our weekly revision lesson or homework check. We can use the knowledge to complete a practice question or use as a key knowledge test.

What I had noticed at KS4 was that knowledge and HW were both issues and so I decided to solve both problems as one. Therefore from January of Y10 they are immediately revising the previous topic. This embeds good revision and homework habits as well as helping them to retain the knowledge from the Germany topic, instead of ignoring it until mocks in June. The expectations are really clear, reducing cognitive load by using the same tasks every week with knowledge test on Friday’s (in back of book). This test focuses on the questions most commonly wrong and will be cumulative. Therefore those that are frequently wrong reappear frequently. I have aimed to create a culture of error within classroom by asking which ones wrong, not right and therefore talking through misconceptions. This provided a depth of knowledge that my students have not previously had.

To conclude, my recommendations for using retrieval practice effectively would be to:

- Specify your knowledge.

- Plan where this needs to be in the curriculum.

- Utilise homework as retrieval time – to consolidate, revise and review knowledge.

- Build routines of retrieval to ensure all accessing and completing.

This blog is taken from my Teach Meet History Icons talk at Chelmsford in October 2023. These resources and recording can be found at the following links:

https://www.tes.com/teaching-resource/tmhistory-icons-event-resources-october-2023-12926175

References:

Leave a comment